Last updated on May 28, 2021

Are birds reptiles?

Birds are more closely related to crocodiles than crocodiles are to lizards or turtles.

Are humans fishes?

Humans are more closely related to a coelacanth than this “living fossil” fish is to any other fish species on Earth.

Are humans monkeys?

You and I are more closely related to a baboon (and “Old World” monkey) than a baboon is to a capuchin (a “New World” monkey).

Are humans apes?

In 1758 Carl von Linné (or Carolus Linnaeus) published the 10th edition of Systema Naturae (“The System of Nature”), establishing the modern method of classifying animals using a binomial system. Linné included all living humans in Homo sapiens (the “wise human”), as a part of the order Primates.

In 1859 Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, concluding that all living forms on Earth—including Homo sapiens—have evolved from a common ancestor through natural selection. The original idea was introduced a year earlier in an article co-authored with Alfred Wallace.

In 1863 Thomas Henry Huxley presented his essay Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature. Huxley compared humans’ anatomy with other primates and concluded that humans should be classified in their own “family” (the “Anthropini”), different from that of “old world apes” (the “Catarhini,” including all the apes, as well as cercopithecoid monkeys). However, he noticed striking similarities with the three great apes: orangutans, gorillas, and chimpanzees* (especially the two latter, the African apes).

In 1871 Darwin published The Descent of Man, in which he elaborated his ideas about human evolution. Regarding the relationships between humans and apes, Darwin concurred with the basic premise of Huxley, further speculating on the group from which humans originated.

The anthropomorphous apes, namely the gorilla, chimpanzee, orang, and hylobates, are separated as a distinct sub-group from the other Old World monkeys by most naturalists.

[…]

If the anthropomorphous apes be admitted to form a natural sub-group, then as man agrees with them, not only in all those characters which he possesses in common with the whole Catarhine group, but in other peculiar characters, such as the absence of a tail and of callosities and in general appearance, we may infer that some ancient member of the anthropomorphous sub-group gave birth to man.

CHARLES DARWIN, THE DESCENT OF MAN. VOL. 1, Pp. 196-197

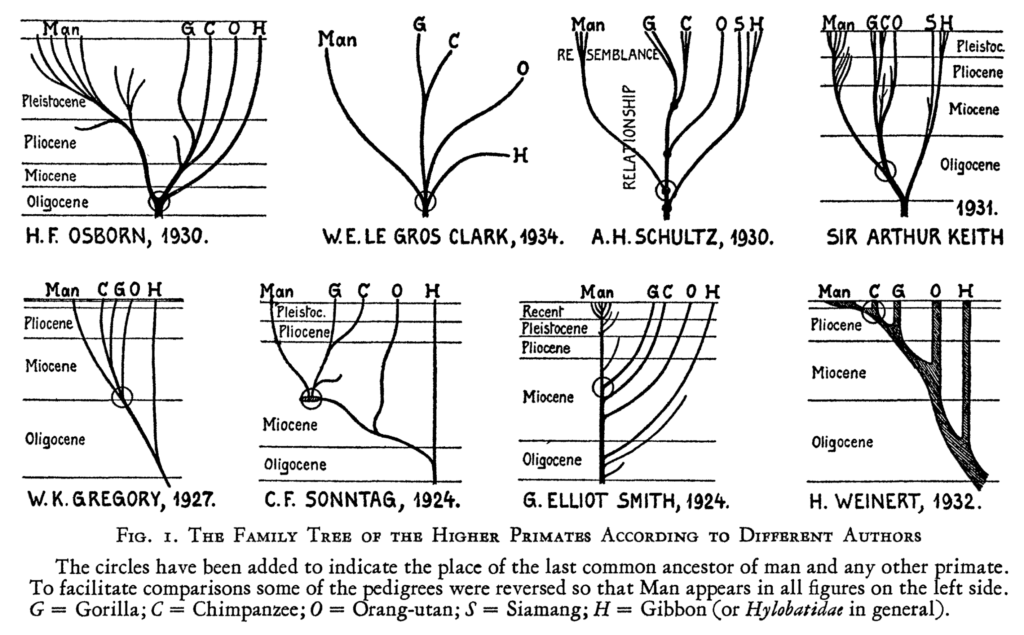

Over the next century, the works of Darwin and Huxley lead to heated debates about humans’ placement relative to living apes. Up until the 1940s, there was no consensus. However, as morphological studies developed, a (sort of) agreement was reached that lasted until the 1960s. Based on their general anatomical similarities, the great apes were considered a natural group called the “pongids” (or family Pongidae). On the other hand, humans and extinct relatives—clearly the oddball in the mix—were the “hominids” (family Hominidae).

Examples of alternative hypotheses about the relationships between apes and humans in the 1930s. From Schultz AH. 1936. Characters common to higher primates and characters specific for man. Q Rev Biol 11:259-283.

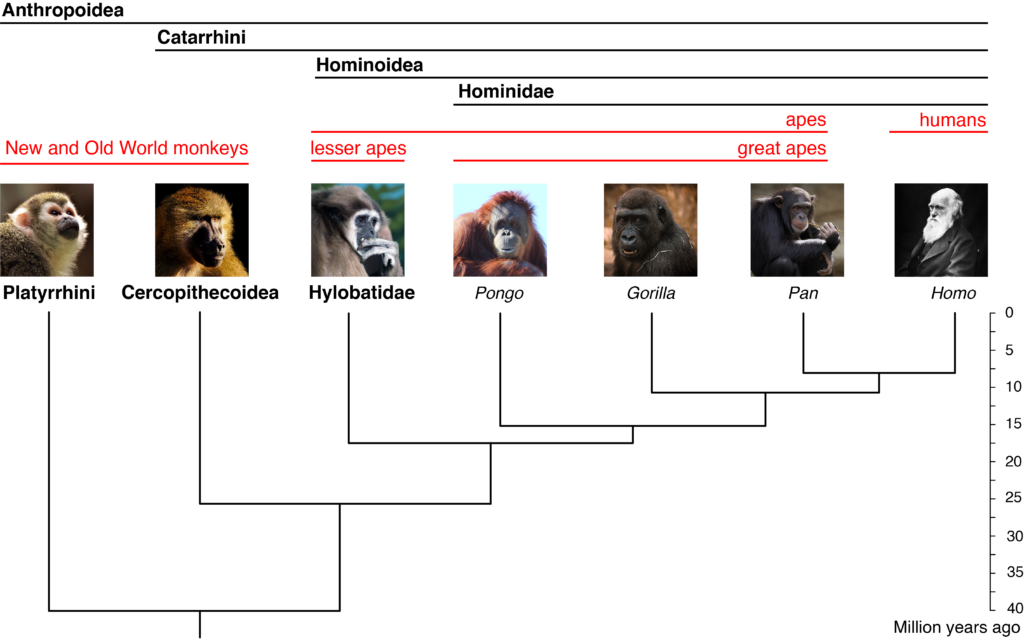

However, starting with immunological comparisons in the 1960s and leading to DNA sequencing studies in the 1990s, the “molecular revolution” created a new paradigm. Genetic evidence now indicates that humans are more closely related to the African apes (gorillas and chimpanzees) than the Asian great ape (the orangutan). Even more, chimpanzees are more closely related to humans than to gorillas! Paleontological and genetic evidence indicates that humans and chimpanzees diverged from an ape ancestor ~9.3–6.5 million years ago, likely in Africa.

Given all the above, most researchers now consider any member of “the great ape and human family” as a hominid. Under this arrangement, humans and our extinct relatives are commonly referred to as the “hominins” (tribe Hominini; see Table 1 below). In other words:

Humans are hominins (e.g., like Australopithecus). Humans are also hominids (like all great apes), hominoids (like all apes), and catarrhine primates. The question—are humans apes?—keeps coming back to me every time I discuss human evolution with anyone. Sometimes, it feels that the question really is: Are humans “special”?

My answer is summarized in the figure below, which I created as a visual depiction explaining the difference between an “ape” and a “hominoid.”

A simplified time-calibrated phylogenetic tree indicated the genetically established relationships among living anthropoid primates. Taxonomic terms are black-bolded, whereas informal (“gradistic”) terms are indicated in red. The adjectives “lesser” and “great” refer to the smaller size of the former relative to the great apes and human group, not old evolutionary notions based on the Scala Naturae. Divergence times are taken from Springer et al., 2012.

Paleoanthropologists use the terms “ape-like” and “human-like” to describe the mosaic morphologies of fossil hominins. For example, the endocranial size of Australopithecus is ape-like. However, its foot is more human-like. These terms do not refer to “natural” groups such as taxonomic categories or evolutionary relationships. These are just informal adjectives that are incredibly convenient when explaining that a given structure is “more like this” and “less like that.” I suggest keeping them like this for the sake of convenience.

I agree with John Hawks on this. For the same reason that birds are dinosaurs but not reptiles, humans are not fishes, nor monkeys—and humans are not apes, either (but have evolved from one!). Are the Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia right, or they need to be updated? In the end, this is all about how you decide to use semantics:

If apes = hominoids, then humans are apes.

If apes = non-human hominoids, then we can add a specific and useful word in our dictionary (as valuable as “reptile,” “fish,” “monkey,” or “dinosaur” are).

Table 1. Linnaean hierarchy of humans within hominoids.

| Category | –ending | example | Informal name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superfamily | -oidea | Hominoidea | hominoid |

| Family | -idae | Hominidae | hominid |

| Subfamily | -inae | Homininae | hominine |

| Tribe | -ini | Hominini | hominin |

This is a commonly used consensus. However, other arrangements are possible.

* I use the generic term “chimpanzee” to refer to both species of the genus Pan: P. troglodytes (common chimpanzees) and P. paniscus (bonobos).

Thanks to David Alba, Marc Furió, Ashley Hammond, Santiago Catalano, Nathan Thompson, and Laia Salles Diez for reading drafts of this.

Primate images were taken from Pixabay: Cover image by Alexas_Fotos, capuchin monkey and gorilla images by Merry Christmas, baboon image by Gerhard G., gibbon image by gayleenfroese2, orang image by ShekuSheriff, chimp image by Susanne Jutzeler, suju-foto, Darwin image by WikiImages.